In the decades since their inception, video games have blossomed from their humble origins into a fully-fledged (not to mention handsomely profitable) art form. Around the world, gamers have been seduced by the power and escapism that digital worlds like Skyrim and Hyrule offer and moved by poignant storytelling in titles like What Remains Of Edith Finch. A large portion of consumers and developers have often trumpeted the belief that games are for everyone. However, for a large portion of the gaming population that belief is a hollow fantasy.

Players with physical disabilities have often turned to third-party manufacturers or outreach groups to create custom (and pricey) controllers just to have a chance to enjoy the video games that able-bodied gamers have played for years. Players with disabilities who are less fortunate have often found themselves excluded from the joys of games entirely. However, the passionate efforts of grassroots activist organizations dedicated to accessibility as well as the prominence of social media platforms have challenged the industry to make the notion that video games are for everyone a reality – a challenge that is finally starting to be accepted in a big way.

The Big Three

For many years, Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft have formed the main road to gaming (at least for anyone who doesn’t own a PC). Even during a time when streaming and digital download options make things a little more complicated, the console is still an accessible notion: a device geared primarily to play games, complete with a controller for you to play them. However, as is often the case, an accessible notion hasn’t always translated to accessibility for everyone.

Those with physical disabilities, particularly disabilities that affect motor movements such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Arthrogryposis, have long struggled with controllers designed and manufactured for players with full functionality in their hands. For years the only options open to gamers with disabilities has been to get creative with custom solutions (such as a Rock Band accessibility kit for wheelchair users) or turn to organizations like The Controller Project to help them craft controllers that accommodated their specific disability.

The Xbox Adaptive Controller, announced in May 2018 by Microsoft, was a huge deal for gamers with disabilities for several reasons. The foot-long controller has remappable buttons as well as USB ports and audio jacks that can be hooked into a wide array of assistive peripherals, giving the user a high level of control when it comes to customizing controls to accommodate various disabilities. This means much more flexibility for controls over the standard controller. For people who felt like they often had to go through backdoors and side channels to enjoy the experiences that were made for able-bodied people, one of the big three console manufacturers putting its money where its mouth was was unprecedented. “What Microsoft has done is truly amazing,” says Paul Lane, a consultant who specializes in video games and accommodation. “To create an assistive hub that allows players from the disabled community to experience gaming is something that needs to be recognized and applauded.” Indeed, gamers with disabilities and developers were ultimately enthusiastic about the device, though some were understandably dissatisfied with the $99 price tag, a $40 increase over the standard Xbox One controller.

According to Bryce Johnson, Inclusive Lead at Microsoft (as well as one of the original designers of the Xbox One), the adaptive controller had been in the works since 2015. “Our mission statement at Microsoft is to empower every individual and organization on the planet to achieve more and we take it literally,” he says. “If you don’t intentionally include people with disabilities in the products you create, you’re actively working against that mission statement.” Johnson’s team worked closely for several years with disability advocate groups like Ablegamers and SpecialEffect to get the proper consulting on the Adaptive Controller, which changed dramatically from its original concept during its three-year development.

The Xbox Adaptive Controller has been heralded as a major step for accessibility in video games but advocates and developers both say there is still work to be done.

Microsoft’s hardware push was easily the biggest bulletin in 2018, and possibly for the past several years, when it comes to accessibility in the world of games. However, Sony has also been embracing the idea of accommodating disabled players – albeit in a much quieter fashion, but one advocates argue is just as important as Microsoft’s showy hardware push. The publisher has been on the forefront of software-related accommodation for years. In 2015, a PS4 system update introduced a number of accessibility-minded functions, including button remapping, text-to-speech, and enlarged texts for those with visual and auditory disabilities. PlayStation first and third-party exclusives also often come with a number of accommodation features. “One thing that has gone unnoticed is what Sony PlayStation is doing within its programming,” Lane says. “Take quick-time events, for example. [In Uncharted 4 and God of War], instead of having a disabled gamer having to repeatedly press a button, the disabled gamer is only required to hold down one button thanks to accessibility features. This really helps a person who has my disability as a lower-level quadriplegic and others who have dexterity challenges.”

Sam Thompson, a senior producer at Sony’s Worldwide Studios, says the company is taking an open-door approach to how it handles disability in the future, but that hardware isn’t in the cards right now. “When it comes to creating and developing accessible experiences, Sony Interactive Entertainment and our WWS teams and development partners have only just begun exploring what is possible,” he says. “Everyone here in the PlayStation family is engaged in creating and delivering accessible experiences for all PlayStation fans everywhere.”

As far as Sony possibly having an adaptive controller of its own one day, Thompson says, “I have to admit, I spent a lot of time this past week at GDC speaking with our friends from Microsoft’s Inclusivity Lab and what they’ve done with the Xbox Adaptive controller is absolutely amazing. We at PlayStation are focusing on accessibility through a different lens, one that looks at the consumer experience from a software perspective, focusing on making our games more accessible by adding meaningful gameplay features to ensure gamers everywhere can share in the experience.”

While it might sound disappointing that Sony doesn’t have anything planned for hardware accommodation, Lane is a firm believer that software assistance is just as vital as any big hardware push: “You can have assistive or adaptable gaming controllers but without the accessibility features of the software you will still have barriers. I believe the same amount of time – if not more – should be devoted to the programming of accessible features inside the games and console – not just gaming hardware,” he says. Lane isn’t alone in that.

God Of War is among Sony’s first-party titles praised for accessibility options.

Johnson cautions that the Xbox Adaptive Controller should not become an excuse for developers not to include software solutions for accessibility: “Our guidance to developers is just to think about doing things like having in-game remapping,” he says. “While the Adaptive Controller does have powerful mapping technology, we feel like having contextual in-game mapping is better for players, so we encourage developers to do that. We want to encourage developers to think about control schemes that people can have fun with a minimal set of control.”

Accommodation advocacy groups have responded enthusiastically to Sony and Microsoft’s efforts to make games a more inclusive space for those with disabilities. The same cannot be said for Nintendo.

“There are other companies like Nintendo who no matter how much we reach out or how many times I rattle the cage in interviews, continue to go do their own thing, blocking gamers with disabilities largely out of their amazing virtual worlds,” Steven Spohn, COO of AbleGamers, says. When I ask about the back and forth with the company, he explains that promising discussions with Nintendo of America about promoting accessibility are always killed when “corporate gets involved.” “We’re not privy to details,” he says. “We have tried reaching out to Nintendo on the corporate level only to be met with silence.”

Much of Nintendo’s marketing rollout for the Switch has been hung on the idea that gaming should be for everyone, with television advertisements dedicated to showing people of all ages taking their Switch wherever they go – playing in living rooms, on rooftops, in garages, with their friends. However, for gamers with disabilities, Nintendo’s inaction has painted a different picture, one of a company that’s willing to engage with an ideal for marketing purposes but apparently has no interest in following through on those notions in a practical, compassionate manner. A brief Google search will reveal a bevy of articles from gamers with disabilities talking about how motion control mechanics games like Breath Of The Wild being impossible to perform, thus barring them from progressing as well as those who lament the lack of options to remap the controls in Splatoon 2.

The Legend Of Zelda: Breath Of The Wild has been criticized by gamers with disabilities for motion controls required to solve puzzles.

We contacted Nintendo for comment about its approach to accommodating those with disabilities; the company issued the following statement: “Nintendo products offer a range of accessibility features, such as haptic and audio feedback, menu designs using grayscale, motion controls, the option to invert colors, and innovative gameplay. In addition, Nintendo’s software and hardware developers are always looking for ways to be inclusive of all gamers, and are actively evaluating different technologies to expand accessibility options in current and future products.”

The Switch is now two years old. In that time, talented gamers have managed on their own to create peripherals that make the Switch more playable for those with certain physical disabilities and concur up workarounds to make the Xbox Adaptive Controller usable with the Switch. However, outside of an update in late April that added a zoom feature for those with visual disabilities, Nintendo has made no public movement on the accessibility front.

The current standings for the big three console manufacturers are cut rather clearly. Despite what disability activists say is Nintendo’s continued refusal to even speak with them in a meaningful way, the exhilaration of Microsoft’s hardware push as well as Sony’s quiet-but-appreciated software accommodation paints a future dripping with possibility for making games playable for more people in the console space. Of course, video games are bigger than just console gaming and so, appropriately, the discussion of disability continues elsewhere too.

In Another Realm

Virtual reality’s resurgence with the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive back in 2016 did not change the industry in the sweeping way ardent supporters hoped for. As developers and platform holders try to iron out solutions for moving around in virtual reality, most current VR experiences are brief games, tourism experiences, or adjacent experiences for non-VR games, like Doom or Skyrim. Still, a number of gamers are tantalized by the potential of virtual reality, especially those with certain disabilities.

“I haven’t walked or stood up in over 26 years,” Lane explains. “When I first tried PSVR, it gave me the sensation that I was up walking and moving. What that did for me mentally is something I will never forget. I thought I would never have that feeling again and I was so happy that I was able to remember how it felt to walk again. PlayStation VR will be able to give disabled gamers an experience they may have never had. Some may never be able to ride a roller coaster, stand, run, and experience life to the fullest. What they can experience with PlayStation VR could change their very outlook and help them to have positive reinforcement in dealing with their disability.”

However, not everyone is as fortunate as Lane when it comes to virtual reality. “VR for people with disabilities is amazing – except when it sucks,” Spohn says. “If you’re somebody who has one hand or limited vision, you’re not going to be able to participate in a lot of what VR has to offer.”

While you can enjoy a number of virtual-reality experiences sitting down with minimal movement (like the card-based Dragon Front), a lot of VR’s premiere titles require constant movement. Beat Saber, Robo Recall, Skyrim VR, Doom VFR are all games that would be difficult, if not outright impossible, for people with motor skill-affected disabilities to enjoy . Furthermore, those without wired headsets often need assistance putting on the gear before they can engage in the game.

With virtual reality developers still constantly fiddling with the nuts and bolts of what VR is capable of in the gaming space, the likelihood of significant disability accommodations in the near future might seem small. However, Jason Rubin, the vice president of Facebook’s VR content (and therefore Oculus’) says the company is aware of the challenges facing disabled gamers and is working to do more in that space. “There’s a lot to do in making VR hardware truly accessible – the range of opportunity is wide, and we have only scratched the surface on what can be done– and growing the user base and ecosystem is a crucial step,” he says. “It’s incredible, as we look toward a future with total accessibility, to see VR content used broadly by third-parties to enable more and more people to experience the magic of video games. Having said that, we can and should do more.”

A spokesperson for HTC Vive says it’s also looking to the future with a focus on making virtual-reality experiences more favorable to disabled players. Vive asserts eye-tracking technology is capable of letting “developers create content that doesn’t rely on controllers,” though the technology is early and not in wide use across Vive’s library.

Virtual Reality is still in its adolescence, with even its biggest proponents saying the technology has a long way to go before it can reach its potential. However, the fact that virtual reality’s biggest players are approaching that future with disability accommodation in mind is comforting.

Making Some Noise

Whatever strides disability accommodation has made in the games industry this past decade is owed largely to a grassroots movement of passionate groups comprised of both those with disabilities and able-bodied allies dedicated to the notion “that games are for everyone” should not be an ideal but a reality.

“The advocacy and work of accessibility specialists and charities definitely goes back 15 years or more. Some have been working toward accessibility in games since the ‘80s,” says Cherry Thompson, an accessibility advocate and consultant. “I think there’s been a slow change happening for that entire time, but the biggest amount of change has definitely happened in the past three-to-four years. We’ll be seeing even more in the future, too. I think the past year it’s been in the mainstream press more, which has lent weight to the movement that’s been happening for a long time. It’s kind of this nice feedback loop – the more progress that happens, the more it’s talked about and then the more progress that happens.”

Beyond organizations like Dager System and Ablegamers, which have been advocating for the causes of disabled gamers for years, a smattering of sites publish reviews speaking to various disabilities. Can I Play That? is a site dedicated completely to games and accessibility, offering opinion pieces written by disabled gamers about their experiences as well as detailed reviews that grade games on accommodating disabilities related to hearing and mobility.

Can I Play That? is one of several grassroots sites dedicated to providing resources to gamers with disabilities.

Like most similar sites, Can I Play That? is a passion project, with little-to-no monetary gain for the people who contribute to it. “I do not get paid and I’ll be the last to get paid once we get to a place where we’re able to pay contributors,” says Courtney Craven, who co-founded the site in 2014 with disability advocate Susan (AKA OneOddGamerGirl). “It would be amazing if I could make this my profession and earn a living from it, and maybe in some years when accessibility has fully become a mainstream thing, but my focus right now is to get to a place where I’m able to pay contributors.” Can I Play That? has a Patreon, but it hasn’t pulled in the numbers yet to make the site a financially profitable enterprise.

Given that Can I Play That? is a volunteer organization without a company’s sponsorship, that’s no surprise and is hardly rare. However, Craven notes that the industry is taking notice of what Can I Play That? does, saying Ubisoft sends copies of games to the site to help out with accessibility reviews. “I’d love to have relationships like this with more studios, every studio to be honest, but I understand that we’re still pretty small and may not warrant the giving out of a review code,” she says. “I have, however, heard from folks representing countless studios that our feedback has informed their approach to accessibility and I’m thrilled by that.”

Slow And Steady, Toward The Horizon

Disability in games is a much different picture than it was five years ago. The topic of exclusion is rapidly becoming a point of contention in the gaming industry on all fronts. The emergence of social media has given a platform to accommodation advocates with disabilities so their voices are heard and broadcasted loudly. Issues in accessibility are cropping up as an industry-wide conversation in a way that was impossible not that long ago.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice recently inspired a passionate, public debate concerning the artistic vision of difficult games and whether or not making them more accessible does harm to such an experience. The discourse drew in responses from noted industry figures like God Of War director Cory Barlog, who tweeted: “Accessibility has never and will never be a compromise to my vision. To me, accessibility does not exist in contradiction to anyone’s creative vision but rather it is an essential aspect of any experience you wish to be enjoyed by the greatest number of humans as possible.”

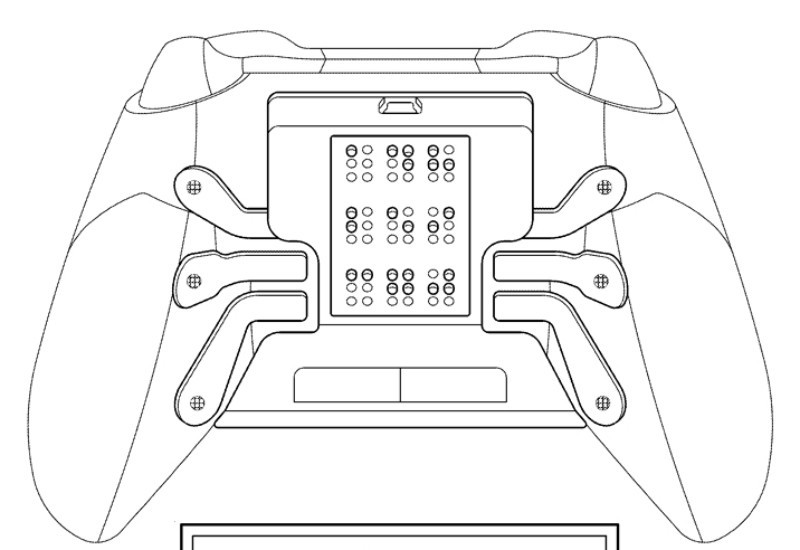

Though the circumstances are brighter than they’ve ever been and the conversation about disability is far louder and longer than ever before, advocates still stress there is much work to be done when it comes to making games accessible for everyone. With E3 around the corner, we might see some more of the fruits of that labor, including a rumored braille add-on for the Xbox One controller. The continued progress, for better and for worse, depends on developers, hardware manufacturers, and publishers listening to disabled gamers with an open mind and a willingness to make changes based on feedback.

A patent for the Xbox One’s rumored braille-add on.

“Listen to the disabled players who need accessibility,” Cherry Thompson advises. “Disabled people understand and know their own needs better than anyone else. It’s impossible to imagine what it’s like to live with any given disability because when you live with it you’re able to adapt to it in surprising and natural ways. Deliberately including disabled players in things like playtesting and user research is just as important as including any other demographic because you won’t design for your whole audience if you don’t include a proper cross section. The wider community of gamers could do with listening to their disabled friends and peers more too as we have a lot of stigma and other issues to deal with. It’s only when we listen with an open and kind heart will we start to change that as a community.”

Craven echoes similar sentiments. “I think the most important thing the industry can do is listen to us, work with us, and learn from us as opposed to simply assuming what you’ve done is good enough,” she says. “And I see that happening. It’s an amazing feeling to see feedback you’ve given over and over again finally appear in a game. So many developers are listening to the community and implementing what we need to make their games as accessible as possible.”